|

Globalization Along Our Border & In Our Backyard

The following presentation was given in November 2000 as a Cal

State Fullerton Geography Department Brown Bag Lecture.

|

I have recently gone on a couple of "Reality Tours" with a human

rights organization called Global Exchange, and I was so amazed at the

things that I saw and heard that so I wanted to bring some of it back

and share it with you.

I have recently gone on a couple of "Reality Tours" with a human

rights organization called Global Exchange, and I was so amazed at the

things that I saw and heard that so I wanted to bring some of it back

and share it with you.

The trip that

I recently went on was to the US-Mexico border where we spent four days looking

at various human rights issues that are becoming especially critical with

the increasing globalization of our border. We stayed in Tijuana,

and during our stay we visited factories ("maquiladoras"), talked to local

activists, heard about environmental problems in the area, and looked at

illegal immigration and the current US program to curb the flow. And

all that we did was really focused on globalization and how the increasing

interaction between our nations is impacting Mexicans who live along our

shared border.

We often

hear about the awesome forces of globalization, and we tend to imagine this

'globalization' thing swarming all around us, causing those 'inevitable'

changes that we so frequently hear about. Yet the more I read about

it and think about it, the less inevitable much of it appears. In fact, there

is nothing inevitable about much of the globalization that is sweeping

across the world. Instead, many such changes are the result of policies

and decisions made by actual human beings. It may seem a silly

point, but it is an important kind of premise to what I am going to talk

about today and what the whole trip was about. When we talk about the human

impacts of globalization, it is important to see the people impacted,

of course, but also see that this isn't some 'natural phenomenon.'

And because a lot of what we call globalization is the result of decisions

by people, not magical, mysterious forces,

those decisions can be questioned--they should be questioned--and reviewed

and assessed as to whether it’s a good system (dare I say "fair"),

and what can be changed and improved.

Of course,

there are many well-known benefits of globalization, and, likewise,

the notion that there are also negatives of globalization is widely acknowledged.

Indeed, most people do acknowledge that there will be some losers in the

"globalization" game. We have all heard statistics, such as...

|

- In Latin

America there are 240 million human beings without the necessities of life,

and this when the region is richer and more stable than ever, and

during a time in which free trade and other hallmarks of globalization

are more present than ever.

- Back

in 1995, Oxfam had economists forecast the benefits to various regions of

the World Trade Organization by 2002. This group of experts concluded

that the European Union will have gained $80 billion from trade liberalization,

while Africa will have lost $2.6 billion.

|

.

So there are clearly

winners and losers in the globalization game, and I am going to talk

about some of the 'losers' today. But one last thought before I do... Many

economists are saying that globalization will, among other things,

extend the Third World model to industrialized countries, creating

a society that is two-tiered-- with a small sector of extreme wealth &

privilege on one end and a large sector of the masses on the other end (the

'superfluous' people). What? The losers of globalization aren't

just 'out there'? They are here? That is something to think about!

There are certainly statistics that seem to support this trend:

.

- According

to a recent Census Bureau report, there has been a 50% increase in the working

poor (people who have jobs but are still below the poverty level).

- The

Lancet , the British medical journal (which is the most prestigious

medical journal in the world) recently published a study which found that

40% of children in New York City live below poverty level, and suffer from

malnutrition and other conditions that accompany poverty.

- The

New England Journal of Medicine (the American answer to the Lancet) recently

studied the mortality rates of black males in Harlem and found that they

average around the same as in Bangladesh!

- Business

Week reports "The gap between high- and low-income families has widened steadily

since about 1980, hitting a new high every year since 1985."

- Lastly,

U.S. Secretary of Labor Robert Reich adds "We have the most unequal distribution

of income of any industrial nation in the world ... we can't be a prosperous

or stable society with a huge gap between the very rich & everyone else."

|

I mention all these

statistics because when I have discussed this notion with people recently,

I generally get a response similar to "No, I don’t believe that."

And maybe these economists who are projecting a

growing income gap in the United States are entirely wrong? There

are statistics to support it, yet we all know that statistics

can be found to support anything. Regardless, I think it is interesting

to consider, and so I have decided to include examples in the US when we

talk about negative impacts of globalization on Mexicans who live along our

border. Because chances are--it's not just "out there." |

One of the main focuses of the trip was to look at the working conditions

in the booming maquiladora industries.

Maquiladoras are foreign-owned factories, about half of which are

US owned, that assemble imported components and raw materials into

finished products, then export the products, mostly to the United

States. There are over 3,000 maquiladoras in Mexico, about a

quarter of which are in the Tijuana area. Employing over one million workers

nationwide, the maquiladoras are an important source employment in much

of Mexico. In fact, in the Tijuana area, maquiladora employment accounts

for over 50% of all jobs! So where better to go than Tijuana to look

at the maquiladora industry and its impacts on the local communities in

which they are found.

One of the main focuses of the trip was to look at the working conditions

in the booming maquiladora industries.

Maquiladoras are foreign-owned factories, about half of which are

US owned, that assemble imported components and raw materials into

finished products, then export the products, mostly to the United

States. There are over 3,000 maquiladoras in Mexico, about a

quarter of which are in the Tijuana area. Employing over one million workers

nationwide, the maquiladoras are an important source employment in much

of Mexico. In fact, in the Tijuana area, maquiladora employment accounts

for over 50% of all jobs! So where better to go than Tijuana to look

at the maquiladora industry and its impacts on the local communities in

which they are found.

|

One of the people we met with was Manuel Garcia-Lepe, the Strategic Alliances

Executive Officer at the Economic Development Department for the State of

Baja California. Garcia-Lepe spoke with us about the maquiladoras

in the area, and essentially gave us the powerpoint presentation that he

gives potential investors. In his presentation, he details the many

benefits of the Tijuana area, including its close proximity to the enormous

and wealthy US market. Maquiladoras are indeed huge here—from

metal stamping, food and beverage, to packaging and electronics. In

fact, Tijuana is the “TV capital of the world”, assembling over

25 million TVs annually. Companies from all over the world have set up shop

along the border zone. American and Japanese brands predominate, and

include 3M, Mattel, Hughes Aircraft, Honeywell, Tonka Toys, Black

& Decker, Fisher Price, Hasbro, Mitsubishi, Sony, Canon, Casio, Sanyo,

Maxell, and Sharp. Korea’s Samsung and Hyundai also have plants,

as do companies from Taiwan, the People’s Republic of China,

Singapore, and eight EU countries. Clearly, these maquiladoras are

a major feature on the landscape and in the lives of those who live along

the border.

One of the people we met with was Manuel Garcia-Lepe, the Strategic Alliances

Executive Officer at the Economic Development Department for the State of

Baja California. Garcia-Lepe spoke with us about the maquiladoras

in the area, and essentially gave us the powerpoint presentation that he

gives potential investors. In his presentation, he details the many

benefits of the Tijuana area, including its close proximity to the enormous

and wealthy US market. Maquiladoras are indeed huge here—from

metal stamping, food and beverage, to packaging and electronics. In

fact, Tijuana is the “TV capital of the world”, assembling over

25 million TVs annually. Companies from all over the world have set up shop

along the border zone. American and Japanese brands predominate, and

include 3M, Mattel, Hughes Aircraft, Honeywell, Tonka Toys, Black

& Decker, Fisher Price, Hasbro, Mitsubishi, Sony, Canon, Casio, Sanyo,

Maxell, and Sharp. Korea’s Samsung and Hyundai also have plants,

as do companies from Taiwan, the People’s Republic of China,

Singapore, and eight EU countries. Clearly, these maquiladoras are

a major feature on the landscape and in the lives of those who live along

the border.

. |

There

is a pervasive belief that "all parties benefit from this industrial

system," as Mexicans gain a significant number of jobs and foreign owners

benefit from Mexico's low wage rates, which average less than 30 percent

of those north of the border. Indeed, it seems like a perfect solution…from

a macroeconomic level.  But, in fact, ALL parties do not benefit from this system. In the United

States, maquiladoras would most likely be called sweatshops. Workers average

six to seven days a week, work 10-15 hour shifts with few breaks, and often

work in conditions that are hazardous to their health. Maybe you are saying…

"Eh, that happens all over the place." And it does. Or you are thinking,

"that looks like a nice, clean place to work". This was indeed a nice

factory—which is probably part of the reason why we were allowed to

tour this one. The technology inside is actually quite impressive, and it

is very clean. Plants that assemble electronic components have to be

very clean, of course. So what could be the problem?

But, in fact, ALL parties do not benefit from this system. In the United

States, maquiladoras would most likely be called sweatshops. Workers average

six to seven days a week, work 10-15 hour shifts with few breaks, and often

work in conditions that are hazardous to their health. Maybe you are saying…

"Eh, that happens all over the place." And it does. Or you are thinking,

"that looks like a nice, clean place to work". This was indeed a nice

factory—which is probably part of the reason why we were allowed to

tour this one. The technology inside is actually quite impressive, and it

is very clean. Plants that assemble electronic components have to be

very clean, of course. So what could be the problem?

In short…workers

at these maquiladoras DO NOT EARN A LIVING WAGE. They don't even come

close to earning a liveable wage. As you can see on this chart, a maquiladora

worker has to work for hours just to buy basic food items. The average

maquiladora worker earns between $0.80 and $1.25 an hour—basically

$50 a week.

Hours of Maquiladora Work Required to Buy Basic Necessities

(1 kg. is

equivalent to 2.2 lbs.)

|

| Beans,

1 kg |

4 hrs |

| Rice,

1 kg |

1 hr,

26 mins |

| Corn Tortillas,

1 kg |

40 mins |

| Chile

Peppers, 1/8 kg |

1 hr,

15 mins |

| Tomatoes,

1 kg |

1 hr,

35 mins |

| Beef,

1 kg |

8 hrs |

| Chicken,

1 kg |

3 hrs |

| Eggs,

1 doz |

2 hrs,

24 mins |

| Vegetable

Oil, 1 ltr |

2 hrs,

25 mins |

| Limes,

1 kg |

1 hr,

20 mins |

| Milk,

1 gal |

4 hrs,

17 mins |

| Toilet

paper, 1 roll |

43 mins |

| Detergent,

1 kg |

2 hrs |

| Diapers,

box of 30 |

11 hrs,

30 mins |

| Shampoo,

10 oz |

2 hrs,

25 mins |

| Elem.

School uniform |

57-86

hrs |

| Roundtrip

bus fare |

1-3 hrs

|

| Cooking

gas, 1 tank |

20 hrs |

| Aspirin,

bottle of 20 |

2 hrs,

25 mins |

(These figures are based on average prices in Tijuana for an

assembly line

worker earning 26 pesos a day ($3.57).)

Mexico is a cheaper

place to live than the United States, true, but not that much cheaper--not

cheap enough to make this meager salary liveable. Tijuana, in fact,

is one of the most expensive cities in Mexico. With rents averaging

more than a maquiladora worker will earn in a month, most maquiladora workers

live in shantytowns that lack basic services like water, sewage, or electricity.

So why do these

factories pay so little? Because they can…and that is what

makes the situation very controversial. These corporations are not

breaking any laws. Most are billion dollar companies, and chances

are most could pay a living wage and still greatly benefit by locating

their factory in this area. A living wage in Mexico is still much,

much lower than the minimum wage in the industrialized nations from which

these companies are based. And paying a living wage would ensure that ALL

parties benefit from this system.

I think it is important,

when studying a phenomenon, to hear from the people who are actually living

it, so I am going to read an excerpt from an interview with a maquiladora

worker, and I will pass out copies of the entire interview at the end.

| "My name

is Maria, and I work in a maquiladora. I am a member of Regional Border

Workers Support Committee. Organizing to demand a living wage

is very important to me because I work as hard as I can, and yet I still

can't make ends meet. I know these U.S. corporations are taking advantage

of the low wages here, and we desperately need these jobs. But they should

pay us enough that we can live and eat decently and send our children to

school." |

She continues

on to discuss the hardships of trying to exist on such meager wages.

And she also raises a good point in her statement, and that is that

these corporations—who are mostly our corporations …the

US corporations that we support with our consumer spending and our

silence—are providing jobs, and when criticisms are made against the

system, people often say “These factories provide much needed jobs.

If the factories weren't there, they wouldn't have a job at all.”

This is surely a statement that could be made about a great deal of foreign

investment in the developing world. And, it can also be stated that

these factories “pay what market requires.” We heard this

quite a few times from the manager we met with at the maquiladora that we

visited. And these statements are true. Again, maquiladoras do

provide much needed jobs, and the factories are able to pay so little because

there are people who are desperate and need the jobs. But it has to

make you wonder where a society should draw the line. When is a company

taking advantage of lower wages in a country that is not as developed as

their home country…and when is that company exploiting the desperation

of those people. Under the current system, these companies are making

massive profits on near-slave wages. Corporations exist to maximize

their profits, but where is the line drawn and by whom.

If the factories weren't there, they wouldn't have a job at all.”

This is surely a statement that could be made about a great deal of foreign

investment in the developing world. And, it can also be stated that

these factories “pay what market requires.” We heard this

quite a few times from the manager we met with at the maquiladora that we

visited. And these statements are true. Again, maquiladoras do

provide much needed jobs, and the factories are able to pay so little because

there are people who are desperate and need the jobs. But it has to

make you wonder where a society should draw the line. When is a company

taking advantage of lower wages in a country that is not as developed as

their home country…and when is that company exploiting the desperation

of those people. Under the current system, these companies are making

massive profits on near-slave wages. Corporations exist to maximize

their profits, but where is the line drawn and by whom. |

In addition to very

low wages, in order to ensure that this 'dream manufacturing environment'

persists for these corporations, workers are also often prevented at all

costs from forming unions and fighting for better wages and conditions.

And, in the absence of unions or adequate systems of regulations, many workplace

violations are prevalent. For example, women are often forced to take

pregnancy tests, either by providing a urine sample or producing a sanitary

napkin as proof that they are not pregnant. Such actions totally violate

Mexican, US and international laws. What was startling to me was the

number of US corporations that were engaging in practices that they would

never dare to do in the United States.

So what are local

and international activist doing to help improve this situation. We

met with six different groups and heard about the work that they are doing

to improve working conditions, such as trying to form unions (or quasi unions),

trying to inform workers of their rights (of which they are generally kept

ignorant), and trying to press for a liveable wage. After listening

to all groups, it was clear that their efforts all really coalesce around

one concept—"work but with dignity."

.

Now,

lest you think that we don't have to worry about that stuff here… (”Good thing we don’t have sweatshops.”) Well,

California has the dubious distinction of being the sweatshop capital of

the nation. The presence of sweatshops in California, particularly Los

Angeles, is partially because the garment industry is so large in California—the

state’s second largest manufacturing industry, and the largest garment

manufacturing area in the United States. On the Los Angeles trip, we visited the LA garment district where I took this photograph just a few months

ago.

(”Good thing we don’t have sweatshops.”) Well,

California has the dubious distinction of being the sweatshop capital of

the nation. The presence of sweatshops in California, particularly Los

Angeles, is partially because the garment industry is so large in California—the

state’s second largest manufacturing industry, and the largest garment

manufacturing area in the United States. On the Los Angeles trip, we visited the LA garment district where I took this photograph just a few months

ago.

When people

today think of "sweatshops," it often conjures up images of the cramped,

dangerous and filthy factories in the early 1900s that plagued US cities--full

of recent immigrant workers & children toiling for long hours in dangerous

conditions. Yet what goes along with those images is the belief that

‘we are done with all that stuff.’ But…sweatshops are

back, and probably never left totally. In fact, sweatshops in California

have become a major problem in last few decades. In "the Alleys" of LA's

garment district, if you go up the unmarked elevators, you see floor after

floor of sweatshops like this one.

The Department

of Labor has acknowledged that sweatshops are a problem. They estimate that

half of all registered garment manufacturers in California pay less than

minimum wage, two-thirds do not pay overtime, and one-third operate with serious

health and safety violations. It is estimated that Southern California

garment employers owe as much as $73 million in back wages to their garment

workers. So why does this problem persist? "Aren’t we in

the clear because we have a law?"

Part of

the problem is that the United States Department of Labor only has 800 inspectors—eight

hundred inspectors to inspect six million worksites of all kinds in the United

States. But a larger part of the problem is that the very structure

of the garment industry encourages the creation of sweatshops. Retailers

buy from manufacturers who generally contract out their work to factories

(contractors). The competitive bidding by these factories for work

drives contract prices down so low that they cannot pay minimum wages or

overtime to their workers, and instead they have to ‘sweat’ the

profits out of their employees. By demanding such low prices

for garments, retailers are unquestionably complicit in the cycle (although

they generally try to disassociate themselves from the contractors, claiming

that they have no control over conditions at factories.)

Thus, all levels of the garment industry contribute to the perpetuation

of sweatshops, and therefore all levels must work (or be pushed) to make

the necessary changes to end such exploitative practices.

|

.

.

Again, we met with activists, such as this gentleman from UNITE, who are

organizing and fighting for better conditions, and working to ensure that

basic standards of workplace safety and compensation are met. And

remember, this is how things changed at the turn of the century. People

joined together and eventually formed a strike—what became known as

The Great Revolt. Eventually, through their efforts the Fair Labor

Standards Act passed in 1930s.

In fact, university students have actually been some of the most vocal

and effective proponents of fair labor practices in the garment industry in

recent years. The United Students Against Sweatshop has been tremendously

effective in working to ensure that university gear—sweatshirts,

hats, jackets—are not made in sweatshops, in the United States or

abroad. The Cal State system and UC system have both received a tremendous

amount of pressure from students, and have made changes in their purchasing

practices because of it. |

So clearly, this issue of exploitative labor practices can be found here

as well.

|

Now, back

to Mexico… The second issue that we looked at is one "contribution"

that some maquiladoras do unfortunately make to local communities,

and that is pollution. Unfortunately,

many foreign maquiladoras do not comply with regulations for the safe disposal

of hazardous wastes, which by US & Mexico law must be returned to the

United States.  By 1995 the border’s maquiladoras were generating nearly 60,000

tons of wastes per year. The US government tracks this waste that is, again,

by law supposed to return to the US. By 1996, just under 8,000

tons were reported to the tracking system-- only 8,000 tons out of 60,000

tons that were generated. And unfortunately, this is no isolated incident.

The World Bank, a friend of large corporations, did a study on the waste

removal rate and found that half of the maquiladora firms in the Ciudad

Juárez area weren’t even in the tracking database to

begin with. So this is a large problem, the brunt of which is born by the

local people who live in the areas around the maquiladoras.

By 1995 the border’s maquiladoras were generating nearly 60,000

tons of wastes per year. The US government tracks this waste that is, again,

by law supposed to return to the US. By 1996, just under 8,000

tons were reported to the tracking system-- only 8,000 tons out of 60,000

tons that were generated. And unfortunately, this is no isolated incident.

The World Bank, a friend of large corporations, did a study on the waste

removal rate and found that half of the maquiladora firms in the Ciudad

Juárez area weren’t even in the tracking database to

begin with. So this is a large problem, the brunt of which is born by the

local people who live in the areas around the maquiladoras.

.

On our trip, we visited one of the most deplorable examples of a United

States-owned maquiladora—Metales y Sus Derividados (Metals and their

Derivatives). This plant was a battery recycling plant and lead smelter

that was open for 22 years. In that time period, the plant developed

a long history of problems associated with their handling hazardous waste,

until eventually it was shut down in 1994. Today, the factory is abandoned,

and the owner, a US citizen, has returned home and has refused to clean up

any of the toxic waste that is spread throughout the area. |

Environmental assessments have found more than 6,000 tons of toxic waste

still in the surrounding area. Substances like lead, sulphuric acid,

and arsenic are not only in the soil of the area, but are also exposed to

the sun, wind and rain. The concentration of chemicals left behind in the

soil is so powerful, in fact, that it is disintegrating the cinder blocks

of this containment wall that was rebuilt just a few years ago. And most

unfortunate is that the plant is sited on a mesa above a neighborhood,

Environmental assessments have found more than 6,000 tons of toxic waste

still in the surrounding area. Substances like lead, sulphuric acid,

and arsenic are not only in the soil of the area, but are also exposed to

the sun, wind and rain. The concentration of chemicals left behind in the

soil is so powerful, in fact, that it is disintegrating the cinder blocks

of this containment wall that was rebuilt just a few years ago. And most

unfortunate is that the plant is sited on a mesa above a neighborhood,  so that the toxic wastes have seeped into the ground and are carried downhill

into the local water supply of this community, Colonia Chilpancingo, which,

until recently, was not informed of the dangers of this factory. Today,

many people from Chilpancingo are suffering from high rates of health problems

such as asthma, skin and eye irritations, and birth defects. Again

we see that “ALL parties are [NOT] benefiting from this system”,

as it is the local communities who are harmed by the pollutants left behind

in their neighborhoods.

so that the toxic wastes have seeped into the ground and are carried downhill

into the local water supply of this community, Colonia Chilpancingo, which,

until recently, was not informed of the dangers of this factory. Today,

many people from Chilpancingo are suffering from high rates of health problems

such as asthma, skin and eye irritations, and birth defects. Again

we see that “ALL parties are [NOT] benefiting from this system”,

as it is the local communities who are harmed by the pollutants left behind

in their neighborhoods. |

This is just one maquiladora of its kind to be closed for failing

to comply with environmental codes. And while surely some maquiladoras

do comply with waste removal standards, this recurring problem demonstrates

a failure of policies implemented under NAFTA to enforce environmental

quality standards, and punish even the most egregious violators. The

environmental codes have been worked out, one of which is that

US corporations must pay for clean up and must bring waste back to

the United States. The rules are there but enforcement mechanisms

either don't have the necessary teeth, or just aren't working. And

unfortunately some foreign corporations know this.

NOW AGAIN, lest you think this is THEIR problem and we don’t have

to worry about that stuff here… On the LA tour, we spent

time looking at environmental problems in the LA area…specifically

the siting of these environmental industries. There is a term some of you

may have heard, and actually I am not sure I am in total agreement with

it. It is the notion of "Environmental Racism"—the idea

that environmental problems are often sited in ethnic communities…communities

that are predominately African- American, Asian-American, or Latino.

A Sierra Club lawyer accompanied us on the tour, and explained that they

have quite a few lawyers devoted to cases that they consider to be "environmental

racism." I tend to think the problem is more about the socioeconomics

of an area than race, as poor communities tend to have little power or voice,

regardless of their ethnicity. However, I do agree with the notion

that polluting industries are much more apt to be sited in areas where the

residents do not have the political or economic might to fight against it.

NOW AGAIN, lest you think this is THEIR problem and we don’t have

to worry about that stuff here… On the LA tour, we spent

time looking at environmental problems in the LA area…specifically

the siting of these environmental industries. There is a term some of you

may have heard, and actually I am not sure I am in total agreement with

it. It is the notion of "Environmental Racism"—the idea

that environmental problems are often sited in ethnic communities…communities

that are predominately African- American, Asian-American, or Latino.

A Sierra Club lawyer accompanied us on the tour, and explained that they

have quite a few lawyers devoted to cases that they consider to be "environmental

racism." I tend to think the problem is more about the socioeconomics

of an area than race, as poor communities tend to have little power or voice,

regardless of their ethnicity. However, I do agree with the notion

that polluting industries are much more apt to be sited in areas where the

residents do not have the political or economic might to fight against it.

What is interesting

is that there is a very pervasive idea that pollution is equitably distributed.

Notions like "we are all in this together" or "the circle of poison" are

a popular and important part of the environmental movement, yet they can

distract us a bit from realizing that there is a pattern of disproportionate

exposure. Yes, ecosystems are interconnected and because of that--we

are all in this together. But when you look at the siting of polluting

industries, they do tend to be in poor areas. To a certain extent,

it’s the chicken and the egg scenario. Is it that the plant

is there and then the income declines as those who can afford to move out

do so, or is it that plants go into areas where people are poor and don't

have enough political and economic power to successfully fight against it.

I think it is probably both. |

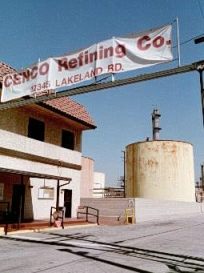

On the tour we visited with community leaders who are trying to fight

against pollution in their area. One community in Santa Fe Springs

is currently fighting to stop the reopening of the old Powerine Oil

Refinery, which was built in the 1930s and had long held the dubious distinction

of being the dirtiest plant in the state of California until it was

eventually closed in 1995 because it was simply not possible to turn a profit

with all the penalties it repeatedly received for environmental pollution.

However, in 1998 the plant was purchased by The Pat Roberson (of the 700

Club fame) Charitable Trust, and was allowed to reopen (under the new name

CENCO) to the surprise of local residents and activists alike. Even

more surprising was the waiving of the required Clean Air Quality Review.

There is a great deal of concern about the reopening of this plant because

the majority of the equipment is old and has been idle, calling into question

its safety. In fact, the safety issue is particularly crucial, as

the refinery will be using hexavalent chronium!

On the tour we visited with community leaders who are trying to fight

against pollution in their area. One community in Santa Fe Springs

is currently fighting to stop the reopening of the old Powerine Oil

Refinery, which was built in the 1930s and had long held the dubious distinction

of being the dirtiest plant in the state of California until it was

eventually closed in 1995 because it was simply not possible to turn a profit

with all the penalties it repeatedly received for environmental pollution.

However, in 1998 the plant was purchased by The Pat Roberson (of the 700

Club fame) Charitable Trust, and was allowed to reopen (under the new name

CENCO) to the surprise of local residents and activists alike. Even

more surprising was the waiving of the required Clean Air Quality Review.

There is a great deal of concern about the reopening of this plant because

the majority of the equipment is old and has been idle, calling into question

its safety. In fact, the safety issue is particularly crucial, as

the refinery will be using hexavalent chronium! |

|

Afterward, we met with residents of South Fulton Village, a senior housing

complex that is located across the street. The group of women who gathered

to meet with us told of how the city and the developers of the housing community

promised that the (then-closed) plant would not reopen, and how they are

very concerned about the impacts of the pollution on the residents

of the complex as well as the children who attend an elementary school

just a quarter mile from the plant. This is a valid concern, as it

is children and the elderly who are the most vulnerable to environmental

pollution. I was impressed by this woman, who proclaimed “I am a fighter,”

and stated that while she has lived her life, she is taking on this fight

for the kids who live in the area and go to the school across the way.

These residents told of a long period of being ignored, until they were finally

able to get some environmental activists to volunteer their time.

Afterward, we met with residents of South Fulton Village, a senior housing

complex that is located across the street. The group of women who gathered

to meet with us told of how the city and the developers of the housing community

promised that the (then-closed) plant would not reopen, and how they are

very concerned about the impacts of the pollution on the residents

of the complex as well as the children who attend an elementary school

just a quarter mile from the plant. This is a valid concern, as it

is children and the elderly who are the most vulnerable to environmental

pollution. I was impressed by this woman, who proclaimed “I am a fighter,”

and stated that while she has lived her life, she is taking on this fight

for the kids who live in the area and go to the school across the way.

These residents told of a long period of being ignored, until they were finally

able to get some environmental activists to volunteer their time.

Often times when

environmentalists start talking about limiting production, people

often proclaim that “it has to be somewhere…After all,

LA is the car capital of the world…Ya know, until we have an alternative

energy source, etc…” And that is true, but it really

is not a matter of 'not having oil refineries and we all revert back to

horse and buggy' or 'having refineries and drive cars but pollute the air'.

There are many things can be done to mitigate the environmental

impacts of polluting industries, such as reconfiguring exhaust stacks,

using different chemicals, and using different processes. And that

is really a crucial part of the struggles against environmental racism,

because most corporations are not going to voluntarily enact these

mitigating measures because they are expensive. So many people are

saying that the lack of power in poor communities is why corporations choose

to site polluting industries in those poor communities, where it is known

that the locals do not have the where-with-all to fight against the plant

altogether or to fight for the mitigating steps that are proven

lessen the environmental impacts. It really is a tragic reality--one that

must be changed--and it was really enlightening to look at the issue and

see examples first-hand.

|

Again, back

to Mexico...Another issue that we looked at, and the last one that

I will be covering today, is the current US immigration policy and our current

tactics to curb illegal immigration

. I bet very few Americans have seen the black steel fence running along

parts of the U.S.-Mexico border. It actually was one of the most

ambitious public works projects in U.S. history, and definitely seems to

give the illusion that the border is finally under control. It was

actually put up quite recently, with much of the material coming from what

was left from the Gulf War. (In fact, the timing of its construction was

particularly galling to many Mexicans, because these fences were erected

in the very year that the United States and Mexico signed NAFTA.

To Mexicans, it appeared that the United States wanted to have it both

ways--opening its border to goods, yet closing it to people.)

The fences

only cover about 60 miles of the border—a border that is over 2000-miles

long-–and are mainly placed in the areas of highest crossing.

Thus, vast stretches of the border remain unprotected, including parched

desert areas and high mountainous terrain where immigration authorities doubted

migrants would try to cross because of the inherent physical dangers of the

terrain. And that is actually the main philosophy behind the current border

control program called “Operation Gatekeeper”--to force migrants

into much more inhospitable and rugged places as a deterrent. This unpatrolled

area includes 6,000-foot mountain peaks, where there's a 50% chance of freezing

temperatures six months out of the year, and vast expanses of desert, often

with 110+ degree temperatures in the shade.

So, whereas

six or seven years ago, when the canyons near San Diego would come alive

at night as thousands of illegal immigrants raced through the underbrush

to get to California, today those canyons are quiet since the launch

of Operation Gatekeeper. Often the

only human presence is that of the occasional Border Patrol agent,

surveying the night with an infrared scope. It is so calm, in fact, that

Border Patrol agents routinely beg to be transferred to livelier parts of

the border.

Operation

Gatekeeper was kicked off when the Army Corps of Engineers came in and built

roads so that agents could get right next to the border and monitor

illegal immigrants before they attempted the crossing. They

also erected stadium-style lighting and instituted sophisticated surveillance

devices like night scopes, helicopters, ground sensors, and video

cameras. But the centerpiece of the strategy was doubling the number of

Border Patrol agents and assigning them to sit at regular intervals in their

stationary vehicles within sight of the border for hours to deter would-be

crossers. And, of course, with all these additions, under this plan the

INS budget zoomed. Since the start of Operation Gatekeeper, the INS

has spent nearly $6 billion on securing our southern border. (The INS

is actually now a larger agency than the FBI.) So again, the ideology

of Operation Gatekeeper is that this increased presence will “force

migrants into much more inhospitable and rugged places.”

Did the

strategy work? Well, the number of apprehensions in San Diego

plummeted—from 531,000 in 1993 to 182,000 in 1999. But the reality

is that the nation's border is far from being "under control." In

fact, there are actually now more rather than fewer illegal immigrants

crossing the border, and there are more illegal immigrants in the United

States than ever before. As a result of the increased difficulty in crossing,

crackdowns have had the perverse effect of

inducing people to begin migrating for fear that conditions at the

border will get even worse, and then inducing them to stay longer

to avoid the hazards of crossing again. The General Accounting

Office, which is Congress' investigative arm, confirms these trends. Migrants

are still crossing, but are moving eastward from San Diego, and crossing

in less defended portions of the border—those really dangerous

areas. To this the INS now admits that they underestimated the determination

of those seeking to cross the border. In fact, the head of the INS

stated “We expected geography to be our ally, but in fact people have

been far more willing to cross in places that are formidable."

And she acknowledged that “Pushing them is the most fundamental

human motivation that exists, which is to eat and support your family and

survive and have a future."

But this

is more than a failed policy.

As I just stated, migrants are still crossing—but now it is

in those really dangerous areas, and the numbers of those who die in crossing

the border has soared from 23 deaths in 1994 to 201 deaths in 1999.

This chart compares the deaths that took place the year before Gatekeeper

began, to the deaths that have happened so far this year.

|

Deaths Under Operation Gatekeeper

|

1994 (prior to

Gatekeeper)

|

1/1/00 -

10/2/00

|

| Hypothermia/Heat

Stroke |

2

|

73

|

| Drowning |

9

|

31

|

| Accident |

11

|

16

|

| Homicide |

1

|

0

|

| Total |

23

|

120

|

.

As you can see,

most of Gatekeeper’s victims died from exposure, either in the

Tecate mountains or from heat stroke and dehydration in the Imperial

Desert. In addition, others have drowned in the All-American

Canal, trying to avoid the worst of the desert.

The following maps show the increasing incidence of death, as well as

the eastward movement of migration, from the first map in 1995 to the second

map of the deaths that have occurred so far this year. As you can see,

the deaths have soared and shifted east into the mountains and deserts.

And...the Border Patrol itself says that no one knows how many bodies lie

undiscovered.

|

maps from www.stopgatekeeper.org

|

Now all of this is in violation

of international human rights law. The Interamerican Commission on

Human Rights considers this policy to be a breach the American Declaration

of the Rights and Duties of Man, and Amnesty International-U.S.A. has overwhelmingly

passed a resolution condemning Gatekeeper.

At present, the United Nations Human Rights Commission is conducting a study

to determine whether it should issue a condemnation.

Now, this is not

a question of whether the US has a right to control the border. NO

ONE is advocating just opening the borders for the free flow of people. Indeed,

few would take issue with the sovereign right of the U.S. to police its

borders. Instead, critics of Operation Gatekeeper are simply imploring

the US to police its borders in a manner which complies with international

human rights obligations--essentially, to police the border in a manner

that minimizes, not maximizes, the threat to life. In fact, when this

case was pending before the Interamerican Commission on Human Rights, the

U.S. did acknowledge that there are limits on a governments right to control

entry into its territory.

Really, most

of these groups, as well as individuals who are opposed to this strategy,

are simply calling for the United States to revert to the pre-Gatekeeper

strategy, pointing out that

|

1) it was no less effective overall than Gatekeeper

2) it was much cheaper

3) the loss of life was much less under the previous strategy

|

In effect, all

that Operation Gatekeeper has achieved, at an enormous cost in lives and

money, is to move the migrant foot traffic out of the public eye and give

the appearance of a border under control. This has even been acknowledged

by The San Diego Union-Tribune, which until recently was a knee-jerk

defender Gatekeeper. The Tribune now has called the program a “dismal

failure,” saying that Gatekeeper has “merely shifted the problem

elsewhere.”

In the

hopes of preventing hundreds more migrants from dying just to keep

up the illusion that the border is under control, many have been

protesting and demonstrating to bring attention to this problem. While in Mexico, I observed and participated in some of the protests,

so I want to take the last few minutes to share some slides from some of

the protests. In spots all along the border wall, activists and those

who have lost loved ones have been memorializing those who have died while

crossing the border. At the point where the wall reaches the ocean

is one of these memorials. On top of the listing of names, there is

a tally of the lives that have been lost under Operation Gatekeeper. And

a question is posed--"How many more?" Reading the names, ages, and

state of origin is a vivid reminder that these aren't statistics--these are

individuals. It was much the same experience as I felt at the Vietnam

memorial in Washington DC, when you are face to face with the names

of those who have died. Quite a few of those who died could not be identified,

so the listing often reads "No Identificado."

While in Mexico, I observed and participated in some of the protests,

so I want to take the last few minutes to share some slides from some of

the protests. In spots all along the border wall, activists and those

who have lost loved ones have been memorializing those who have died while

crossing the border. At the point where the wall reaches the ocean

is one of these memorials. On top of the listing of names, there is

a tally of the lives that have been lost under Operation Gatekeeper. And

a question is posed--"How many more?" Reading the names, ages, and

state of origin is a vivid reminder that these aren't statistics--these are

individuals. It was much the same experience as I felt at the Vietnam

memorial in Washington DC, when you are face to face with the names

of those who have died. Quite a few of those who died could not be identified,

so the listing often reads "No Identificado." |

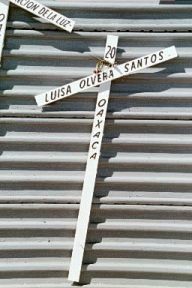

| In addition

to this memorial and protest, at points all along the wall, crosses

have been put up, each with a name of someone who has died since the

start of Operation Gatekeeper. Every death is a tragedy, but it was

especially sad to see the young children who have died (as the crosses

bear not only the names but also the ages of those who died.) As with

the other memorial and protest, quite a few crosses simply said "No identificado." |

|

|

| On the

weekend that we were there, a protest march was taking place and we were

able to participate in part of the 16 mile "desert walk" and then take

part in the ceremony held to honor those who died. As with the other

protests, each individual death was remembered, as participants took

turns placing stickers bearing the names of those who died on a large

wooden cross. |

|

In Mexicali, we helped an organization called the

Border Art Workshop with their memorial, which commemorated those who

have died by placing a water jug along the wall for each individual.

Water jugs were chosen because many of the deaths are due to dehydration in

the harsh desert environment. Again, this and other protests really

aim to reinforce the human component of the US's current border control

efforts. The point is not to call for an end to all border control

measures, but to urge the US government to take the necessary steps to ensure

that our policies are not intentionally putting people 'in harms way.'

In Mexicali, we helped an organization called the

Border Art Workshop with their memorial, which commemorated those who

have died by placing a water jug along the wall for each individual.

Water jugs were chosen because many of the deaths are due to dehydration in

the harsh desert environment. Again, this and other protests really

aim to reinforce the human component of the US's current border control

efforts. The point is not to call for an end to all border control

measures, but to urge the US government to take the necessary steps to ensure

that our policies are not intentionally putting people 'in harms way.' |

.

In conclusion, I

was just reminded by someone before coming in here that it’s

a lot easier to criticize something that to promote something positive.

This is true. But if there are problems, they need to be

looked at critically. They need to be criticized and scrutinized since that

is how you come to the solution. The point of my presentation

today is not to say 'look at these poor Mexican workers; their

wages are so low.' Or 'look at his poor community that has been polluted

by this US corporation.' Instead, I want to promote the notion that

we need to look at these issues honestly and critically, because we need

to develop effective international strategies so we can

overcome these problems. And while I haven't provided any grand answers

to these problems today, I hope I have communicated to you what I think are

some real issues that we most certainly should devote our energies to resolve.

At least I know I will be.

To return to

Betsy's homepage, click here

To return to the

Global Exchange website, click

here

|

|